Surviving Black and Latino families are seeking $2 billion in reparations for being systematically pushed out of Palm Springs, Calif., about a 100 miles outside of Los Angeles, in favor of wealthy white people.

State officials have called the Section 14 area of Palm Springs a “city-engineered holocaust,” and city officials in 2021 apologized for the state’s role in gentrifying a diverse space more than half a century ago.

In the 1950s and 1960s, in a similar manner to how racist whites burned down a neighborhood called “Black Wall Street” in 1921, promptly referred to as the Tulsa Race Massacre in Oklahoma, Palm Spring, a selective real estate development, was raided by racists.

The destruction of Section 14 was capitalized on by developers and city officials who wanted to rebuild and revitalize the area and abandon the people who lived there first. The city did not offer Black and Latino people the opportunity to own homes, and there was no legal process, but robbed them of the chance to build wealth and destabilized their families for generations.

“I’ll never forget the cowardice of the act of our family being displaced, herded off like cattle and sheep, having to move from house to house,” Delia Ruiz Taylor, the daughter of Mexican immigrants whose family moved to a racist neighborhood, told The Los Angeles Times.

Taylor told The Los Angeles Times that white children participated in the house burnings and raids, yelling racial slurs and shooting her with a pellet gun as her family fled for safety.

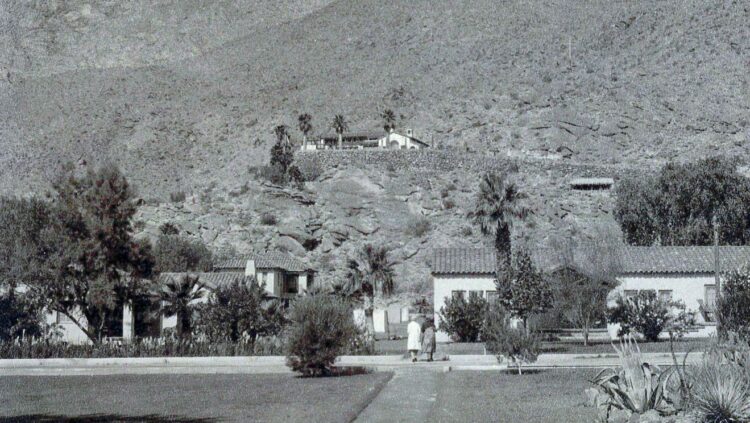

Between 1930 and 1965, part of the land in Riverside County was placed in trust to become a 6,700-acre Indian reservation owned by the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians. The problem was the downtown property, 646 acres of which belonged to Section 14, had a Black and Latino population not willing to cooperate with corporate demands.

Families of color rented lots in Section 14, one of the few places without restrictive covenants and housing discrimination. They began to build a community of homes, churches, and more.

Land leases were unattractive to developers because there were trust rules that restricted developers to five years.

These restrictions got in the way of officials who envisioned hotels, shops, and other businesses for the land, and they began plotting to take control.

Declaring the area a slum helped bring about changes in federal law in the mid-to-late 1950s that eased restrictions on tribal land, allowing 99-year leases, and the city of Palm Springs, especially then-Mayor Frank Bogert, facilitated the eviction of Section 14 residents, including the destruction of homes and personal property, so that the Section 14 property could be developed commercially, The Desert Sun reported.

When asked why he removed people from their homes in 2001, Bogert told The Los Angeles Times, “I was scared to death that someone from Life magazine was going to come out and see the poverty, the cardboard houses, and do a story about the poor people and horrible conditions in Palm Springs.”